Edito

Eline Dehullu – Editor-in-chief A+

Stéphane Damsin and Jan Haerens – Co-editors

Shared authorship in practice

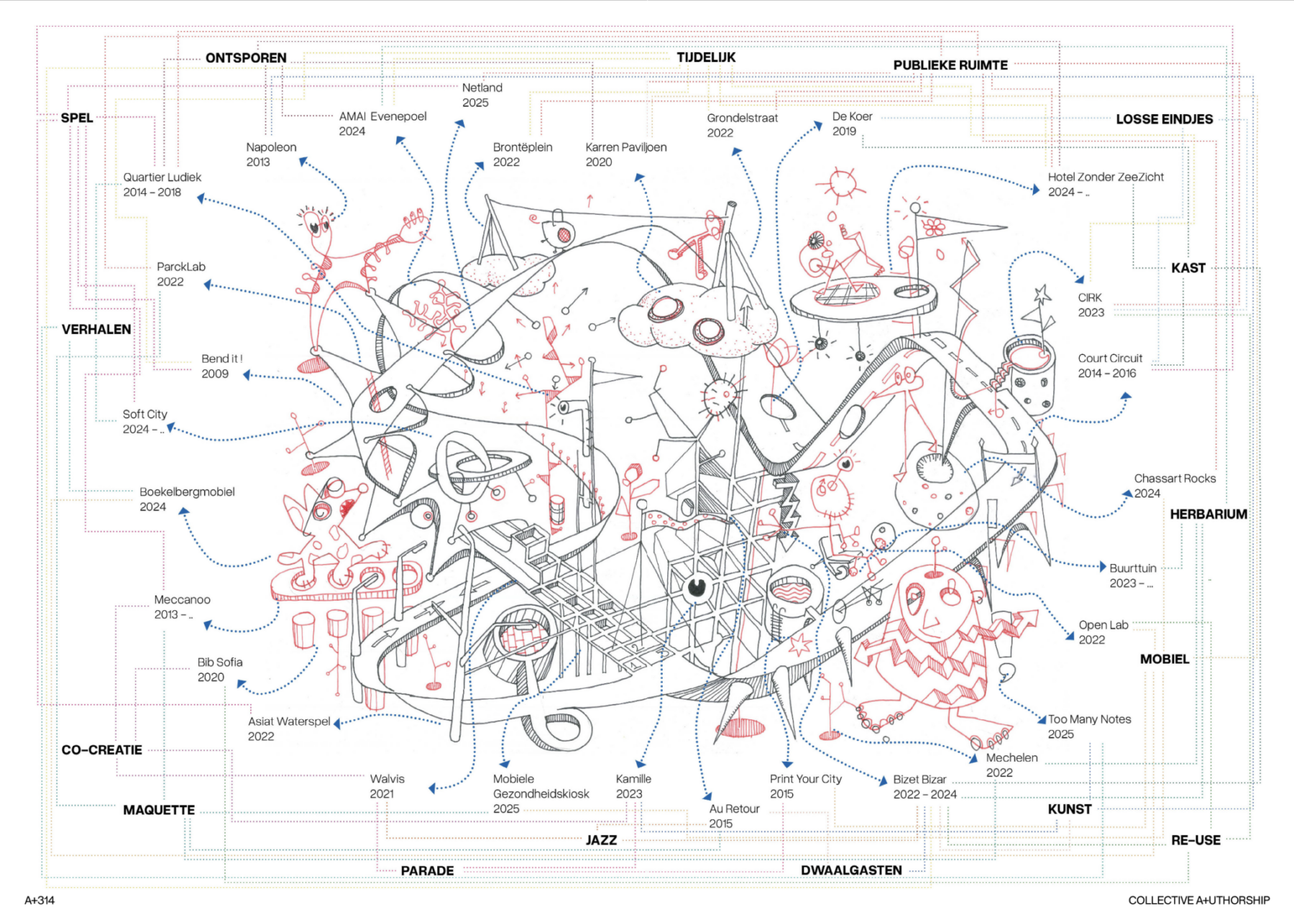

Curated by Stéphane Damsin and Jan Haerens of the Brussels architectural firm Ouest, the exhibition Urban Legend will open on 15 October at Bozar. Drawing on stories from urban planners, artists and writers, they will present their vision of the city as a living organism. On the occasion of this show, they contributed to this issue of A+ on co-creation and shared authorship, a transdisciplinary approach in which non-architects are actively involved in the design and construction process.

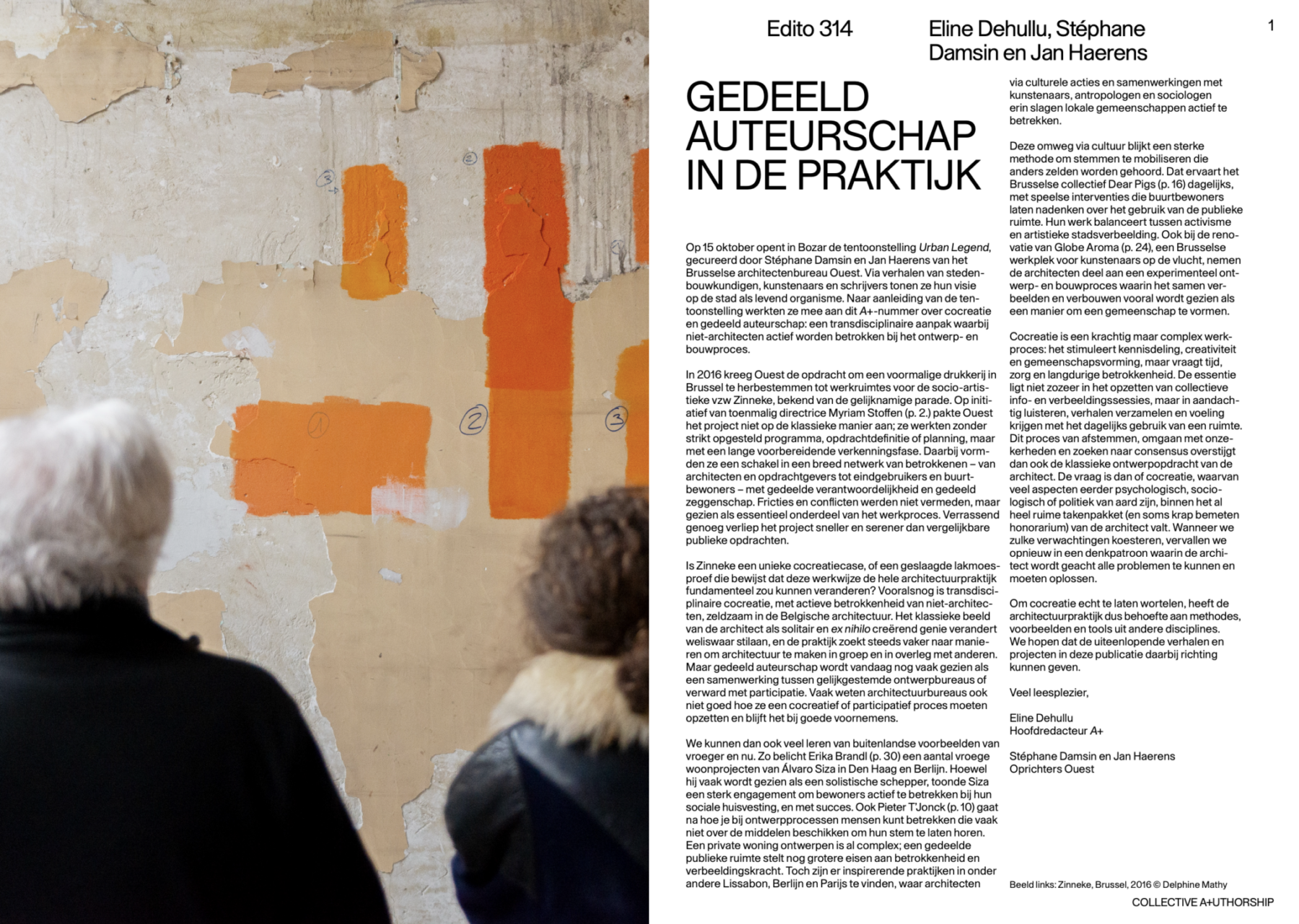

In 2016 Ouest was commissioned to repurpose a former printing workshop in Brussels into workspaces for Zinneke, the socio-artistic non-profit organization known for the parade of the same name. On the initiative of then director Myriam Stoffen, Ouest took a novel approach to the project; instead of working with a strictly defined programme, assignment definition or schedule, they opted for a long preparatory and exploratory phase. In doing so, they became a link in a broad network of involved parties – from architects and clients to end users and local residents – with shared responsibility and shared control. Friction and conflict were not seen as something to be avoided, but as an essential part of the process. Surprisingly, the project proceeded more quickly and more smoothly than many comparable public commissions.

Is Zinneke therefore a unique case of co-creation, or a successful litmus test that proves that this approach could fundamentally change the entire architectural profession? As yet, transdisciplinary co-creation, with the active involvement of non-architects, is rare in Belgian architecture. The classic image of the architect as a solitary genius creating out of nothing is gradually evolving, and the profession is increasingly looking for ways to create architecture in a group and in consultation with others. However, shared authorship is still often seen as a collaboration between like-minded design offices or gets confused with participation.1 Also, architectural firms often ignore how to set up a co-creative or participatory process and therefore often fail to follow through on their good intentions. 1 Participation is the process whereby citizens are actively involved in local government decision-making through information, consultation and advice. Whether driven by democratic ideals or electoral motives, politicians support this process. Participation and co-creation can go hand in hand, but require clearly outlined definitions to avoid confusion.

We can learn a lot from foreign examples past and present. Erika Brandl sheds light on a number of early housing projects by Álvaro Siza in The Hague and Berlin. Although often seen as a solo creator, Siza showed a strong commitment to actively involving residents in their social housing, and with success. Pieter T’Jonck examines how one can use design processes to involve people who often lack the means to make their voices heard. Designing a private home is complex enough; a shared public space places even greater demands on involvement and imagination. Nevertheless, inspiring examples can be found in Lisbon, Berlin and Paris, among other places, where architects have managed to actively involve local communities through cultural actions and collaborations with artists, anthropologists and sociologists.

This detour via culture is proving to be a powerful method for mobilizing voices that are otherwise rarely heard. This is something the Brussels collective Dear Pigs experiences daily with playful interventions that encourage local residents to think about the use of public space. Their work balances between activism and artistic urban imagination. In the renovation of Globe Aroma, a Brussels workplace for artists in exile, the architects are also participating in an experimental design and construction process in which imagining and converting together is seen primarily as a way of forming a community.

Co-creation is a powerful but complex work process: it stimulates knowledge sharing, creativity and community building, but it requires time, care and long-term commitment. The essence lies not so much in setting up collective information and imagination sessions, but in listening attentively, collecting stories and getting a feel for the everyday use of a space. This process of attunement, dealing with uncertainties and seeking consensus therefore transcends the classic design brief of the architect. The question is therefore whether co-creation, many aspects of which are psychological, sociological or political in nature, falls within the architect’s already rather broad range of duties (and often rather limited fee). When we harbour such expectations, we fall back into a mindset in which the architect is expected to be able to solve all problems and is required to do so.

In order for co-creation to really take root, the architectural profession therefore needs methods, examples and tools from other disciplines. We hope that the range of stories and projects shown in this publication will help to point the way forward.

Table of contents

COLLECTIVE A+UTHORSHIP

Edito – Shared autoship in practice

Eline Dehullu, Stéphane Damsin and Jan Haerens

Is Going Alone Always Faster?

Myriam Stoffen

A Different Kind of Architect

Pieter T’Jonck

Interview – Public Space as a Playground: Lieven De Cauter in Conversation with Dear Pigs

Amber Vermaete

A Home for Collective Imagination

Annelies Augustyns and An Vandermeulen

Participatory Housing Models

Erika Brandl

Unity Is Strength

Anne-Catherine De Bast

Opinion – Marginalized Dream

Omar Kashmiry

PROJECTS

XDGA

Mobilis, Brussels

Baumans-Deffet – Dirix

Val-Benoît, Liège

Barozzi Veiga – TAB

Abby, Kortrijk

FELT

Provincial Court, Bruges

Vanden Eeckhoudt-Creyf

Masui 186, Schaerbeek

Dierendonckblancke

Condor, Molenbeek-Saint-Jean

Multiple

Browning, Herstal

Interview – EM2N: Pragmatic Idealism

Eline Dehullu

Sponsored Feature – Vande Moortel: Circular Brick

Arnaud De Sutter