Edito

Eline Dehullu – Editor in Chief

Time as a design parameter

‘We never design for a programme; we use the programme as a pretext to define a structure capable of shifting. Buildings survive because they can resist time physically, but also because they can adopt new functions. We build what must endure, and we set conditions for everything that may change.’ Renowned Portuguese architect Manuel Aires Mateus reflects on what flexibility in architecture means to him. ‘True ecological quality lies in this combination of endurance and openness.’

Buildings that can adapt to new functions, changing users and social evolutions have a longer lifespan. In the quest for sustainability, it is therefore not surprising that ‘flexible design’ is on the rise. The term is widely being used by both architects in competition proposals and project developers in sales campaigns. But what exactly does it mean?

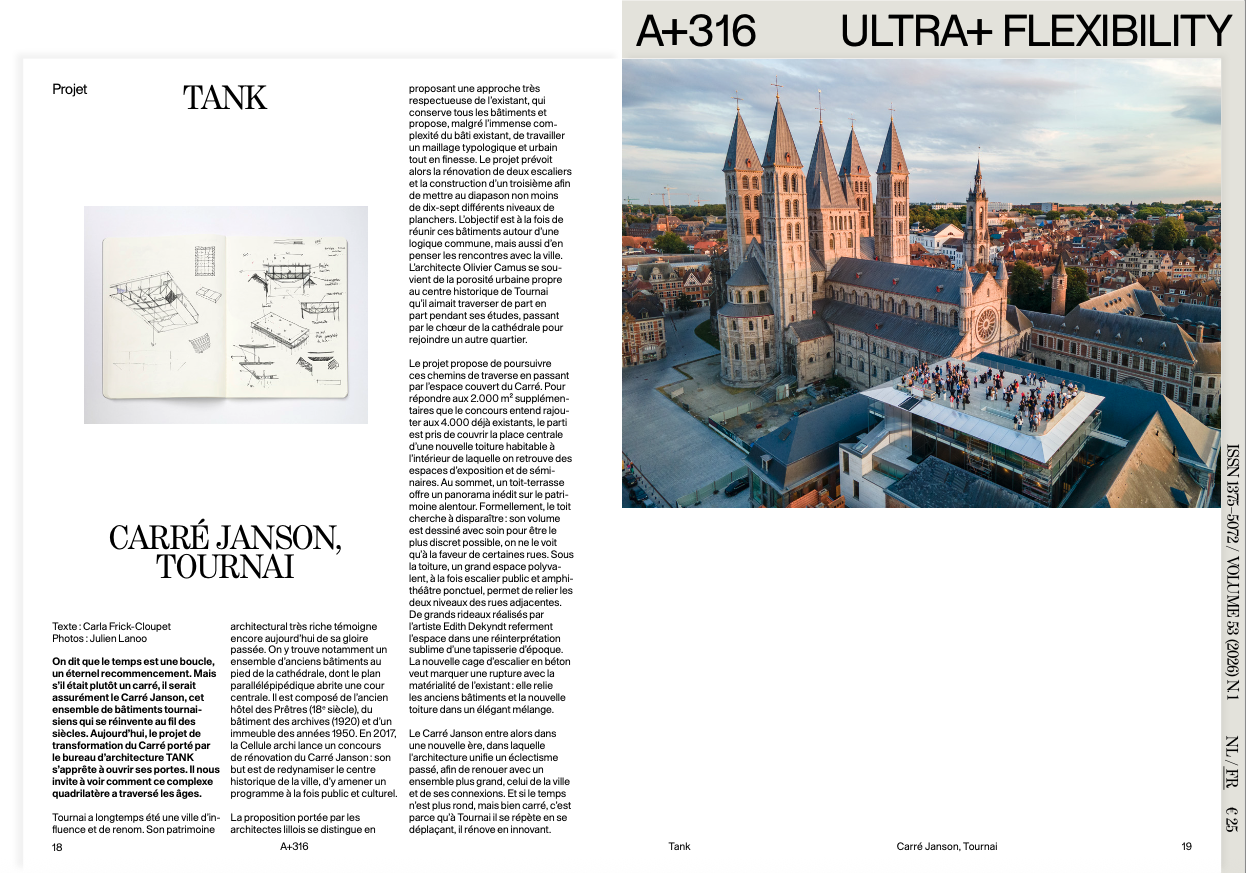

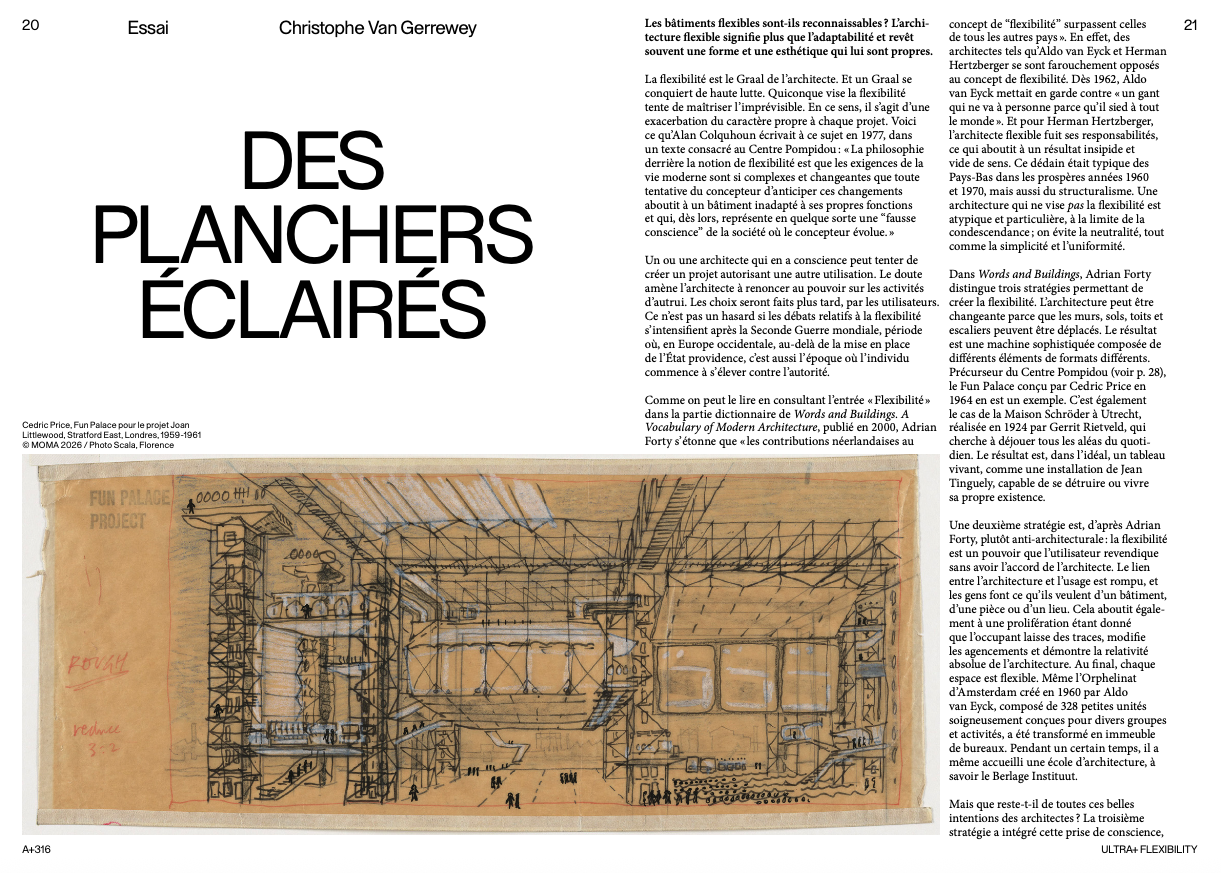

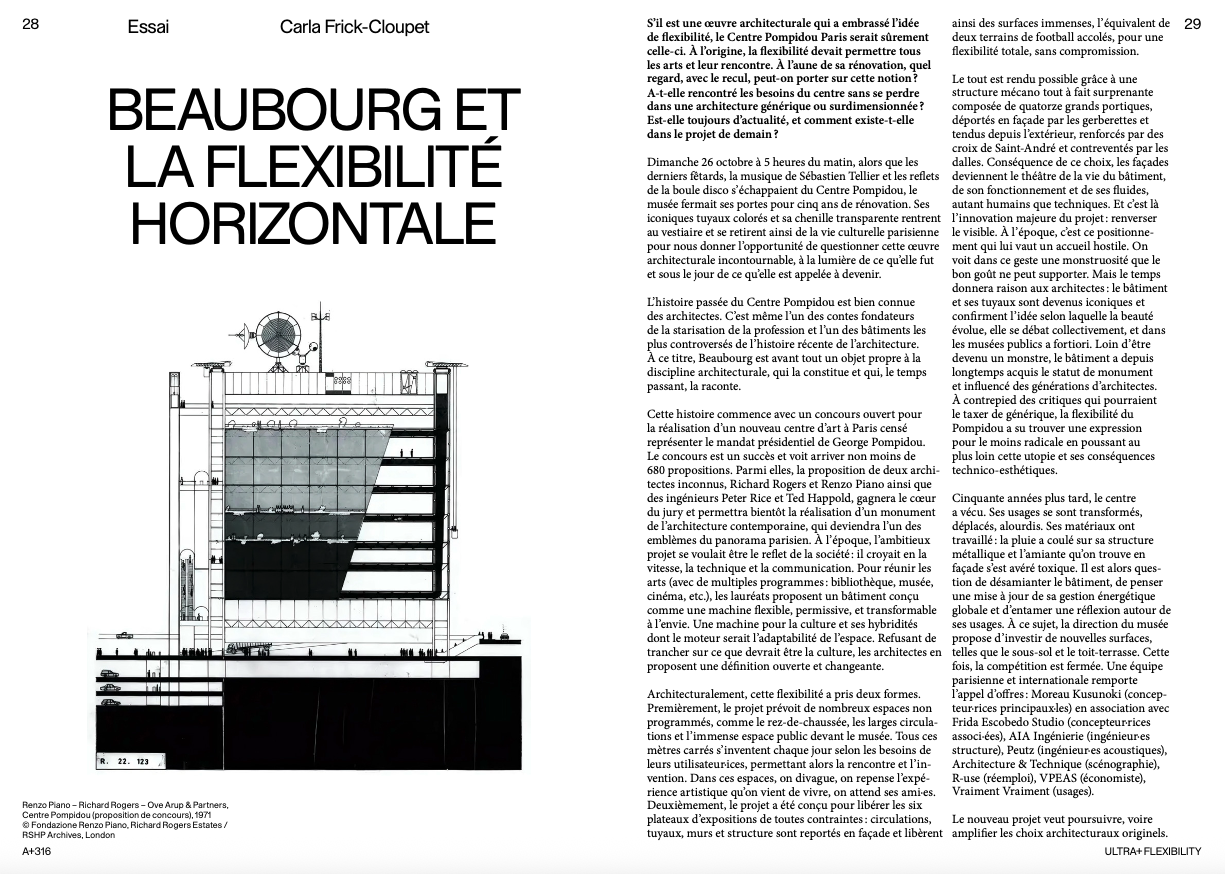

Flexible architecture is not a new concept in architectural history. With his ‘free plan’ and ‘illuminated floors’, Le Corbusier introduced in the 1920s already the idea that a building could change significantly over time. However, it was not until the 1960s and 1970s, at a time when modernist ideas were being called into question, that flexibility made its way into architecture and the surrounding discourse (Michaël Bianchi and Xavier Van Rooyen). In Japan, Metabolist architecture emerged, focusing on flexibility by designing buildings as growing, adaptable organisms. In the Netherlands, Aldo van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger were seen in those years as both pioneers and critics of the concept. And in France, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou in Paris became the building par excellence that embodied the idea of flexibility (Carla Frick-Cloupet).

Both then and now, flexibility in architecture appears to be both promising and disputable. The first reason for this is probably that the term itself is equivocal and can therefore mean very different things. All contributors to this issue attempt to conceptualize the term by searching for precise definitions and appropriate terminology to describe it and grasp what it means concretely. It is all the more remarkable that in their research, carried out independently of each other, they arrive at virtually the same conclusion. Whether it concerns social housing projects (Élodie Degavre and Gilles Debrun), public buildings such as schools (Guillaume Vanneste), recently completed projects (Louis De Mey) or historical examples (Christophe Van Gerrewey), flexibility manifests itself, according to them, in three main approaches. The first is that of temporariness, shiftability and movability. The second strategy revolves around light structures, modularity and expandability. The third interpretation, paradoxically, concerns heaviness, solidity and firmness.

The latter approach brings to mind the ‘intelligent ruin’ of the late architect and first Flemish Government Architect bOb Van Reeth (1943–2025). He coined this term, probably not by chance, in the 1970s; in his view, a building need not be more than a rough and robust structure that can be adapted to the requirements of the client and the age. Recent projects by contemporary architects such as Xaveer De Geyter (XDGA) and Adrien Verschuere (Baukunst) go back almost unconditionally to this concept. However, there are pitfalls. For this interpretation of flexibility is often tantamount to deliberately oversizing the structure so that the building can accommodate future programmes. This excess – in terms not only of space, but also of load-bearing capacity and span – can lead to greater material extraction and costs, which goes against the very idea of sustainability. And that’s not all. With ‘intelligent ruins’, a different kind of aesthetic is also emerging: buildings that can do everything but are nothing in particular often seem bland and generic. They are at once ‘lucid and illusionless’, Van Gerrewey concludes.

The promise of adaptability may come up against financial, technical, aesthetic and social limits, but there is still beauty in the idea for all that. After all, flexibility embraces emptiness, uncertainty and humility. This is perhaps its greatest value. Not as dogma, but as an invitation to see architecture as an open story, one that can be rewritten by time, use and context. As Manuel Aires Mateus puts it: ‘We are not designing for the moment of inauguration; we design rules, thus are working for the first chapter of a much longer story. In that sense, the building is always slightly ahead of us, waiting to be discovered by those who will live in it.’

Eline Dehullu

Editor-in-chief A+

Table of contents

ULTRA+ FLEXIBILITY

Editorial – Time as a Parameter

Eline Dehullu

Essay – Anticipating the Unknown

Louis De Mey

Gilles Debrun and Élodie Degavre

Essay – Illuminated Floors

Christophe Van Gerrewey

Essay – Beaubourg and Horizontal Flexibility

Carla Frick-Cloupet

Essay – Free Teaching Methods, Docile Spaces

Guillaume Vanneste

Essay – Inhabiting Impermanence and Singularities

Michael Bianchi and Xavier Van Rooyen

Opinion – An Imaginary Encounter

Sophie Delhay

PROJECTS

Delmulle Delmulle

51N4E

Tank

Havana

Central

URA

BC Architects

INTERVIEW

Dominique Pieters

COMPETITION

Pieter T’Jonck